1950 Bentley Blizzard Roadster

In 1950 Rolls-Royce’s Chief Projects Engineer, Ivan Evernden, had an idea for a two-seat Bentley sports car called the Blizzard. This year, that dream finally came true – and we’ve driven it.

WORDS: NIGEL BOOTHMAN

PHOTOS: GREGORY OWAIN

EVERNDEN’S DREAM BENTLEY BLIZZARD DRIVEN!AT SPEED IN THE ROADSTER BENTLEY COULD HAVE BUILT

Handcrafted two-seater takes to the road at last

It’s not often a road test article needs to begin by explaining to readers what the subject car is, but in the case of the Bentley Blizzard, the origin story is everything. We announced the completion of the first road-going, fully functional Blizzard in our July/August issue this year. In case you missed that, allow us to fill you in. The car is a realisation of an idea from 1950 by Ivan Evernden, then Chief Projects Engineer at Rolls- Royce. He and John Blatchley are thought to have guided designer and painter Cecily Jenner, who created the only surviving sketches of a two-seat open roadster, based on a Bentley Mk VI chassis and mechanical components.

“The engine is a masterpiece; it’s very smooth and very potent, and the peak power and torque figures of 207bhp and 280 lb ft really mean something”

These sketches inspired father-and-son team Stephen and Chris Pearson of Chesman Motorsport to work with R-type and S-series Continental experts Padgett Motor Engineers and create the real thing, as part of a limited series of 15 hand-built cars. The finished article is remarkably like the sketches Jenner produced. Turning a few pencil portraits into a motor car – and a truly Crewe-standard, productionised motor car – has been an immense task over several years. But finally, in the summer of 2023 the first Blizzard was ready for the road. After a few hundred shakedown miles in the hands of its builders, it was our turn. The Blizzard is built on an original Bentley Mk VI chassis and running gear, modified in some important ways.

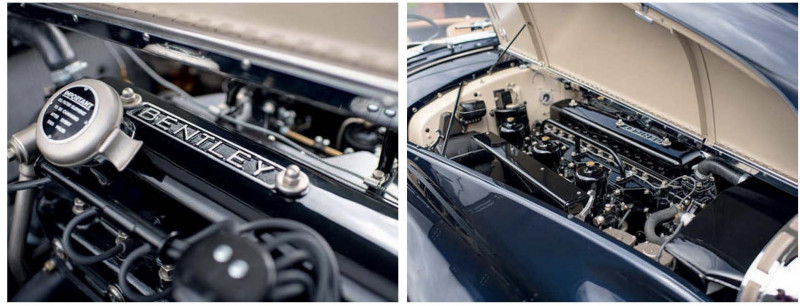

First, the wheelbase is reduced to suit a two-seat sports roadster. Second, the original-spec engine is rebuilt to 4.9-litre capacity and in triple-carb, big-valve tune, as proven by Padgett’s rally-developed Continentals for many customers. Third, this debut example uses a Getrag five-speed all-synchromesh manual gearbox with a central change, which makes a lot more sense than a right-hand change lever blocking one of the car’s two little doorways. On top of this chassis is constructed an entirely new body, based on a steel floor but with aluminium sub-structures supporting hand-made aluminium panels. There is, at least for this first example, no provision for even a folding roof – this is a sunny-day car.

Evernden had an obvious target when he released the brief brochure proposal for the Blizzard: Jaguar’s XK120 had taken a quantum leap over other post-war sports cars both in looks and performance. Wasn’t it reasonable that Bentley should compete? After all, they were keen to maintain or even expand the high-performance image of the Silent Sports Car. In the end, of course, that desire took flight as the R-type Continental and the Blizzard never went beyond the sketches. Until now.

MEETING THE MYTH

First impressions are of a wide, almost muscular shape nosing out the garage at Padgett’s workshops in Lincolnshire. It may have a similar side profile to the Jaguar, but the track of the front and rear axles is unaltered from the Mk VI and R-type saloons, and it gives the Blizzard considerable presence. Its face is unmistakably Bentley, coming straight from the designers who had already created the Mk VI and would go on to style the S-series. The colour, a very dark blue, starts to catch the light and reveal some beautiful, swaged lines flowing through wing and door, and again through the rear quarter. Considering there aren’t really any sketches that show the rear treatment of the Blizzard, the team has done a fabulous job with this. I think it’s my favourite angle on the car – the wing-top creases ending in little two-lamp clusters, below which the bumpers kick out to form neat veepoints.

Even the badging and brightwork details are totally convincing, so it’s hard to spot what’s borrowed from other Bentleys and what’s new. Jack Sandall, workshops manager at Padgett Motor Engineers, gives us a few hints. ‘There are bits of various Crewe cars in it,’ he says. ‘More or less standard R-type front lights and vents, with a pair of the R-type Continental-style overriders – the early kind – on bumpers we’ve designed to suit the body, front and rear. The radiator within the shell is shorter, but thicker to make up for it. The radiator shell is brand new – made in brass and then chromed. The windscreen frame is a mix of solid and folded brass, all chromed.’

Proprietor Jeremy Padgett shows us around the inside of the car, beautifully trimmed in tan hide. ‘The dash is based on a standard Mk VI/R-type, with walnut veneer, just configured into the cockpit shape. The curvature of the top of the bulkhead and screen is our own work, because there was never a drawing for the dash. It has all the instrumentation a Continental would have.’

The neat double row of bonnet louvres is an idea from Bentley’s Hythe Road development team, who tried them on the Contintentals in period, though it didn’t go into production. Padgett’s often put them on rally prepared cars, as even in the standard car the floor and bulkhead can get quite warm, so getting rid of some under-bonnet heat is a good thing. Jeremy says the paint shop don’t like this feature – much patience is required to finish them this nicely!

GET IN AND GET GOING

Even the steering wheel is special, with the centre being original in basis but the rest re-made a little smaller. Even though it’s a lesser diameter, it’s been engineered to release with a catch (hidden in the original hand-throttle and choke sliders!) and then slide off like a race wheel. Jack brings one over in its raw state, made in round steel bar for the spokes and the rim, with a cast centre – though they’re now being machined out of billet. It’s then covered in a resin-like plastic that does a fine job of imitating a 1950s wheel.

Rear-hinged ‘suicide’ doors are there for ease and elegance of access, and they do offer more space to enter than a front-hinged alternative. However, I’m about to run into my big problem with the Blizzard, because as I wriggle into the driver’s seat it becomes apparent that this car isn’t built for people my size. Confession time: I’m 6’5” (1.98m), which is at the upper end of what sports car designers allow for now, never mind 70 years ago. This isn’t the first two-seat roadster I’ve struggled to fit into. But by removing the seat squab, I can get kneeroom enough to drive the car safely – it’s just a little firm under the posterior!

That’s a shame, because it’s a lovely place to be, otherwise. The dash veneers are exquisite, with some book-matching between the central panel and those at the sides, with only the modern-looking shiny steel gearknob catching my eye as something out of place. Starting is accomplished with a conventional choke-pull for the triple SUs and a push of the button, which brings the inlet-over-exhaust straight six to life immediately. It sounds very Bentley. The team resisted the temptation to make it into a noisy, rorty machine and there are three silencers in the system, producing a mellow note, even under acceleration.

Jack says they’re thinking about removing one box, but I’d be willing to bet this is exactly how Bentley would have specified it. Silent Sports Car, and all that. There is no power steering, and it’s not needed, either. At somewhere around 1250kg, the Blizzard is half a ton lighter than a Continental and three-quarters of a ton lighter than a Standard Steel saloon. With the old system in as-new condition, it’s so nicely engineered it needs no assistance even at parking speeds. Pulling away into the lanes, the steering feels quicker than normal for a Mk VI. Jeremy says the steering is still the standard ratio, so perhaps it’s the reduced rim diameter that I’m noticing. It’s a lovely helm to control.

The limited space in the cockpit is still bothersome in some ways, as the dash controls are partly obscured by the steering wheel and reading the centre-mounted gauges isn’t as easy as in a saloon or a Continental as you’re closer to them here, making the angle much steeper. The windscreen feels low and close to my head, though Jack tells me they’ll be changing the rake for the next car and moving it forward an inch. Those are the negatives done with.

We’re out on the open road now, and it drives really well, feeling beautifully screwed together with a definite Bentley sensation about it – that hasn’t been lost in the creation of a lighter, more sporting car. The engine is a masterpiece; it’s very smooth and very potent, and the peak power and torque figures of 207bhp and 280 lb ft really mean something. We’re so used to hot hatches or performance SUVs producing 300, 400 or even 500bhp that 206bhp in a sporting car might seem lukewarm. It isn’t, especially in a car that weighs 1250kg and is, in every way bar the more modern gearchange, a product of the 1950s. That’s 40bhp more than a Jaguar XK120, 75bhp more than the Aston-Martin DB2 drophead and 100bhp more than the strikingly Blizzard-like Alvis TB21 (see box-out, right), all of which would have been seen as rivals in 1950. Of course, Bentley wasn’t getting this kind of output from their 4.2-litre and ‘Big Bore’ 4.6-litre engines back then, even in Continental specification, but they were getting 175bhp by the time the 4.9 engine arrived in 1954 – and all Padgett’s power increases are based on research started at the Hythe Road works. If Bentley set out to build an out-and-out sports car, you can be sure they would have made it fast enough to spare any blushes.

There is instant torque, wherever you need it. I haven’t used 5th gear yet, on this fast cross country run, and it must be a pure motorway gear. The brakes are powerful and pull up straight and true, but I keep getting distracted by how fast the Blizzard wants to go. It would be interesting to drag-race an E-type, never mind an XK. But perhaps making a car in which raffish young men (or unfit old editors!) would dice with Jaguars wasn’t quite the Bentley image – was that another reason the project never got off the ground?

When there’s room, I can discover how tall the gearing really is. With fifth engaged, it’s doing less than 2000rpm at 70mph. It handles well too, steering accurately and responsively to the point of feeling nimble – when has anyone used that word about a Bentley? The key point is this: it feels like a sports car. Not a grand tourer, or a boulevard cruiser, but a sports car. That’s the success of the project. We never knew what a genuine two-seat Bentley sports car of the 1950s would feel like – and now we do. The ride compromise is ideal. They’ve recently stiffened the rear springs and that seems to have hit a fine balance between body roll, which is well controlled, and a supple ride. It’s a hugely convincing package.

BLIZZARD IN BUSINESS

There’s a hurdle to clear if you’ve fallen for the Blizzard, and it’s not insignificant. The costs of developing a limited run Bentley from little more than fag-packet sketches (albeit very nice fag-packet sketches) is vast, as is the quantity of hours needed to put it together. To own one, you’ll need a ball-park figure of £1 million. Before you fall off your chair, remember they’ve been doing a giant 3D jigsaw with only one glance at the box. Those sketches were pretty, but not functional, so they’re had to imagine and then engineer a great many of the structural and engineering solutions you need when building a new car. It’s much more than rebodying a standard chassis or building a special because not only has the wheelbase changed but so has the bulkhead height, and everything that flows from that. Only this time, what’s being built is a not an imitation of a Cricklewood Bentley or a basic racing special, it’s a productionised road car. That’s an immense challenge.

Jeremy, Jack, Stephen Pearson and Chris Pearson and their teams have all gone to the greatest lengths to ensure a Crewe-like standard of fit and finish. Perhaps they’ve occasionally gone a little too far with the bespoke approach, such as the removable steering wheel. If you’re in a place where it helps to devise a removable wheel, perhaps you have an issue with ergonomics. There’s no way Bentley would have sold a car with that feature, and indeed, the team already increased the size of the cockpit over the drawing, because there simply wasn’t enough room. Could they have gone further? You could argue that faithfulness to these drawings has caused too much of a compromise in cockpit accommodation, and if I spent my lottery win with Blizzard Motor Cars, I’d be asking for the rear axle to move back six inches. This kind of build is a remarkable, unlikely thing to complete, and yet by chance we have something in a similar orbit elsewhere in the magazine – the Bensport La Sarthe. Both the Blizzard and the La Sarthe are nominated in the Historic Motoring Awards for Bespoke Car of the Year, which is a fantastic sign of health in this corner of the industry.

The Blizzard deserves to succeed. Not just for the bravery, the engineering integrity and the fabulous finish, but for the purity of their attention to Evernden’s concept. Like all concepts, it may need a tweak or two before it’s right for everyone. Luckily, at this rarefied end of the market, each Blizzard can be built exactly as the owner wishes, and my little gripes will blow away like dust in the wind. Oh, and if you’re thinking that a million pounds is mad for a hand-built, high-speed Bentley roadster that doesn’t even come with back seats or a roof, let me remind you about a car called the Bacalar. This is Bentley’s limited run of 12 handbuilt, high-performance ‘barchettas’, even faster than the W12-engined Continental GTC on which they’re based. It too has just two seats…and no roof of any kind. The price? £1.5m, and they all sold before they were finished. It's a strange feeling to meet a new classic car, but that’s exactly what the Blizzard is – an instant classic, and not because it’s based on a 70 year-old chassis. It’s more like a lost Beatles album or an undiscovered Monet canvas…it fits right into a masterful body of work but it’s thrillingly new at the same time. It’s remarkable and it’s been a privilege to experience it.

“It handles well too, steering accurately and responsively to the point of feeling nimble – when has anyone used that word about a Bentley?”

THE ALVIS ‘BLIZZARD’ – WAS BENTLEY RIGHT?

The Alvis TA21 followed much the same pattern as the Bentley Mk VI: it was a conservatively styled, well-engineered saloon with some sporting credibility from the marque’s reputation and a powerful straight-six engine. It was a bracket down from the Bentley in price and image, but nonetheless comparable. In 1950, when the TA21 was introduced, it was sold alongside another new three-litre Alvis, the TB21. This was a two-seat convertible sports version based on the same chassis and mechanical parts. It had a traditional upright grille and little rear-hinged doors, with an overall look that is undeniably Blizzard-like. Did Evernden see it at the 1950 Motor Show and think ‘Bentley should do that’? Pure conjecture. But if the Alvis’s sales are anything to go by, Bentley made the right choice in in deciding not to go ahead with the project: while more than 2000 TA21 and TC21 saloons were sold, only 31 TB21s found a home.

Jeremy Padgett talks us through the fine detail Three two-inch SU carburettors for potent power. Jack Sandall has put hundreds of shakedown miles on the Blizzard.

Amazingly faithful real-life rendering of the original side-profile sketch Broad haunches suggest the power and performance the car offers Spats swing out on cantilevered hinges.

“Turning a few pencil portraits into a motor car – and a truly Crewe-standard, productionised motor car – has been an immense task over several years”

Snug but undeniably attractive cockpit is beautifully finished Book-matched timbers typical of attention to detail. The original sketch of the Blizzard.