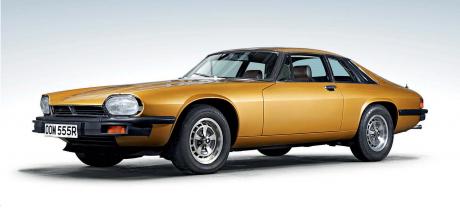

Jaguar XJ-S

The XJ-S went on to be a major success for Jaguar, but its gestation was troubled and its early career blighted by poor sales. We take a look at those early problematic days of the 1970s… Words: Paul Guinness. Photography: Kelsey Archive.

JAGUAR XJ-S GESTATION / MARQUE HISTORY

Paul Guinness tells the story of a difficult birth

The fact that the E-type was a huge success for Jaguar meant a major dilemma when it came to eventually replacing such an iconic design. The problem with success is… what comes next? In much the same way that a best-selling debut author might have trouble writing their second book, or a successful singer might dread the prospect of their second album being panned by critics, whichever car came along to replace the E-type faced one of the biggest challenges in the motor industry.

In fact, a successor for the E-type was being explored long before that model’s Series III incarnation appeared in 1971, with studies created as early as ’67. Developed under model code XJ21, the project is widely regarded as being at least partly inspired by a design worked up by a young Jaguar apprentice of the time, Oliver Winterbottom.

With his aspirations to join the styling department, Winterbottom had entered a competition organised by design house Bertone called the Concorso Grifo d’Oro and in August 1966 was astonished to discover that he had won the prize. Promoted to staff stylist, Winterbottom was then formally engaged on the project to produce an E-type replacement, providing design support under project leader Malcolm Sayer. The brief required using the then newly-developed V12 engine as well as a V8 that was in the works, but the project would always play second fiddle to the need to put the XJ6 into production, with resources correspondingly compromised. In the end, of course, XJ21 was cancelled in favour of the V12 E-type.

Also significant was another Bertone project, a show car for the 1967 Earl’s Court Motor Show, created with assistance from Jaguar and sponsorship from the Daily Telegraph. The concept, styled by Marcello Gandini, was given the name Pirana and bore a striking similarity to the Lamborghini Espada (another Gandini design) that would be unveiled the following year. Built on the bones of an E-type 2+2, the Pirana is cited by former Jaguar designer Nick Hull as an influence on the project codenamed XJ27, which was destined to reach production as the XJ-S.

Rather than looking back towards the E-type era, Sayer’s proposal was to create a modern-looking car in the ‘low and wide’ Italian style. Both Sayer and Winterbottom produced proposals for the car, with Sayer’s using popup lamps and a Jensen-style glass hatch, while Winterbottom went for a fastback style. It was Sayer’s design that provided the essential basis of the production car, but his untimely death in 1970 meant that it would be left to the rest of the team to finish off the details, inevitably aided and abetted by Lyons himself. The glass hatch had already been questioned on engineering grounds owing to its complexity, and before Sayer’s passing had been replaced by the buttresses that would become a signature XJ-S feature.

Work proceeded during 1970, with the pop-up lamps and sleek, low nose of the early proposals being replaced by a conventional grille and large headlamps. The final drawings were produced in December 1971, although they’re notable for the lack of bumpers, which were still missing on the first running prototypes that would be completed the following year. Early styling models used slender chrome items with neatly integrated overriders, but the production cars would feature chunky rubber-trimmed items that met current regulations but were unloved by the design teams at Jaguar.

Winterbottom himself had moved to Lotus in 1971, meaning that the final production version of the XJ27 did have something of a ‘designed by committee’ background. The car employed the platform of the original XJ saloon, albeit shortened by six inches and with the front suspension moved forwards to keep the proportions neat.

IN WITH THE NEW

Wisely, Jaguar left a gap in its sports car timeline between the E-type and its successor, with the final example of the former rolling off the line in 1974. The XJ-S wouldn’t be announced until September of the following year, with Jaguar keen to ensure there were no retro references to the E-type at the newcomer’s unveiling, making the period between the two models something of a handy hiatus.

It was inevitable, however, that comparisons would be drawn, hence the controversy that surrounded the XJ-S. It didn’t help that the threat of American safety legislation ensured Jaguar’s latest sportster was available only as a hard-top coupe. And not everyone appreciated the newcomer’s styling, particularly those trailing buttresses running down the rear wings from the back window. Then there was the fact that the XJ-S would feature Jaguar’s less-than-frugal 5.3-litre V12 engine, at a time when the most recent world energy crisis and soaring oil prices were fresh in the minds of just about everyone Against such a backdrop, surely there couldn’t have been a worse time for launching an upmarket V12-engined coupe? Well, maybe. But at least the XJ-S came with the latest version of Jaguar’s biggest power source, which for 1975 – in the XJ12 saloon – had been re-engineered to accept a Lucas- Bosch designed fuel-injection system, resulting in a substantial improvement in economy despite offering extra power.

Even so, the XJ-S was faced with a number of challenges, summed up succinctly by Jeff Daniels in his famous 1980 book, British Leyland: The Truth About the Cars. Daniels explained: “Alongside the revised XJ12 there was soon to appear the XJ-S coupe, which… was intended to inherit the mantle of the E-type. There was, however, a sense of unease that it should be regarded this way. For one thing, it was not a convertible. For another, it was far more expensive, even allowing for a year’s roaring inflation, than the E-type had ever been. Even more to the point, its styling did not excite the same admiration that had been enjoyed by the older car.”

Some critics went further, damning the XJ-S for its hardtop-only approach as well as for its overall appearance. Compared with the original and perfectly proportioned E-type, also styled by Malcolm Sayer, the XJ-S arguably looked awkward. And this was a point not lost on Jaguar historian Philip Porter, writing in his Jaguar XK8 book in 1996: “No-one could deny that the XJ-S was technically excellent, but it committed one cardinal sin, especially for a Jaguar. It lacked great beauty. Compare it with the XK120 and the E-type – Jaguar threw away all of its wonderful styling heritage. It may have been a factor that by this time Lyons was of advancing years and Sayer was not a fit man…”

Sayer’s death in 1970 – at the age of just 54 – saw Doug Thorpe take over as head of the XJ-S project, even though he wasn’t convinced by the controversial buttresses that so dominated both the profile and the rear-end styling of the newcomer.

LYONS’ INFLUENCE

As already mentioned, development of the XJ-S continued in earnest throughout the early 1970s, against a backdrop of industrial strife and financial disaster at British Leyland. And in the early stages the plan was to offer both hardtop coupe and convertible versions of the newcomer, codenamed XJ27 and XJ28 respectively, to ensure a model range befitting of an E-type successor. However, the likelihood of new legislation being introduced in the USA – which would have prevented any new convertibles being sold there – saw XJ28 cancelled. And by the time that threat of a ban on convertibles subsided in 1974, it was too late for the XJ-S; Jaguar’s crucial new model would be launched in hardtop guise only. Yet still the question remained: why did this upmarket new coupe have to look quite so controversial? Part of the answer lay in Jaguar’s desire to make the XJ-S the most aerodynamic car in its class. Jaguar founder Sir William Lyons explained: “We decided from the very first that aerodynamics were the prime concern and I exerted my influence in a consultative capacity with Malcolm Sayer. Occasionally I saw a feature that I did not agree with, and we would discuss it. I took my influence as far as I could without interfering with his basic aerodynamic requirements and he and I worked on the first styling models together.”

But there were legislative reasons behind certain aspects of the XJ-S’s styling as well, said Lyons, which meant numerous restrictions compared with the early ’60s and the launch of the Sayer-designed E-type: “We originally considered a lower bonnet line but the international regulations on crash control and lighting made us change and we started afresh. Like all Jaguars we designed it to challenge any other of its type in the world – at whatever price – and still come out on top”.

The rear buttresses added both strength and aerodynamics to the XJ-S and proved to be a major talking point throughout the car’s early career. Interestingly, Lyons also claimed that at any customer clinics where prototypes were shown without those buttresses, the results were less than favourable. It seems that despite initial reactions, the XJ-S’s most talked about styling feature was more beneficial than many pundits gave it credit for…

INITIAL FAILURE

The XJ-S’s early years proved to be less than positive, with the model struggling to make its presence felt in the global coupe market. The following decade would see an improvement in its fortunes, of course, aided by an expansion of the range to include convertible and six-cylinder versions. But until then, the XJ-S found itself attracting little interest. In fact, after just five years – and with Michael Edwardes now in charge of the whole British Leyland empire – the XJ-S was in danger of being dropped from the range. Annual sales had fallen from an early peak of 3890 cars in 1977 to just 1057 in 1980, putting the XJ-S on the critical list.

Part of the problem was arguably that the XJ-S wasn’t a sports car – not in the stripped-out two-seater sense, hence some onlookers’ view that it was a poor substitute for such forebears as the XK120 and original E-type. Critics accused it of being too much of a grand tourer, a car capable of effortlessly dealing with pan-European jaunts but without the thrills of such rivals as the Porsche 911. And even in the XJ-S’s later years, the old complaint that “it’s no E-type” would still crop up in conversation. A fair point? Well, no. Anybody who criticises the XJ-S for that is ignoring what the E-type itself had become during its own career. There’s no denying that the inaugural E-type of 1961 was a raw machine with real sports car credentials and the excitement of a headline-grabbing 150mph top speed. But by the time it had evolved into Series 3 guise in 1971, it was a V12-engined grand tourer available as a 2+2 coupe or a convertible. Crucially, the latest E-type was bigger, heavier and softer than its predecessor of a decade earlier. In reality then, the new XJ-S of 1975 was replacing a machine remarkably similar in concept. And while many Jaguar fans will always prefer the last-of-the-line E-type to the earliest XJ-S, not least when it comes to styling, the conceptual differences between the two cars are perhaps far fewer than many people assume. In the end, of course, XJ-S devotees went on to have the last laugh, with their favourite sportster enjoying total worldwide sales of 115,413 cars and a 21-year career – a figure far in excess of the 72,223 E-types that managed to find buyers during its fourteen years on sale. The XJ-S may have endured a rocky start to its career, but its later success proved beyond all doubt the potential of that highly original design.

TEASER!

Our very own Jim Patten has tracked down this early prototype to a North American location. It contains many experimental elements including a horizontal radiator – apparently less than successfully! Jim is researching the history of this car in conjunction with Ed Abbott, a former Jaguar senior development engineer who was responsible for the car in period. We will reveal all in a future Classic Jaguar feature…

BERTONE PIRANA

Created with assistance from Jaguar and sponsorship from the Daily Telegraph was Bertone’s Pirana, based around E-type 2+2 underpinnings and making its debut at the 1967 Earl’s Court Motor Show. Bodied in steel (albeit with an aluminium bonnet) and styled by Gandini, the resultant creation wasn’t exactly pretty but it was exotic looking. The car was transported to Earl’s Court in time for its big reveal and soon became a magazine cover star the world over. The Pirana cost a rumoured £20,000 to build (around £370,000 adjusted for inflation), although it was only ever going to be a show car. The Pirana’s outline proved influential, however, proving influential in the development of the Lamborghini Espada.

“...the XJ-S was technically excellent, but it committed one cardinal sin, especially for a Jaguar. It lacked great beauty.”

“Wisely, Jaguar left a gap in its sports car timeline between the E-type and its successor...”

One of the proposals for XJ27 was this GT coupe based around the platform of the XJ saloon

The buttresses were integral to the design early on, partly to improve the car’s aerodynamic qualities

An early example of an XJ-S prototype, showing an overall look remarkably similar to that of the eventual production version

As the model destined to be the XJ-S gradually took shape, different front-end treatments were experimented with