25 Years Porsche 911 996

Watercooler moment 25 years ago, the Porsche 996 attempted to replace the iconic 33-year-old 911. We drive the bargain Carrera 2, ultra-reliable Turbo and collector-grade homologation GT3RS to see whether they make great classic buys today.

Words SAM DAWSON

Photography JONATHAN FLEETWOOD

A quarter-century on, has the watercooled 996 truly emerged from the classic 911’s shadow?

Watercooler Moment As the car that reinvented Porsche, the 996, hits a quarter-century, we drive Carrera 2, Turbo and GT3 RS variants as racer Jörg Bergmeister and tuner Phil Hindley talk winning, engineering, and making them even faster

‘Could the 996 possibly meet the lofty standards its predecessor spent 30 years setting?’

It’s hard to believe now that the three iconic 911s we’ve gathered today were once the products of a company in trouble. Porsche – a luxury sports car firm, of all things – is one of the most valuable marques in the world nowadays. Its combination of motor sport-bred desirability, family-saloon reliability and ease of ownership thanks to relative mass production means its wares are as profitable as some bestselling hatchbacks. This new phase began in 1997 with the 996, but should you buy one 25 years later? The entry-level Carrera 2 can be yours for as little as £10k. The mighty Turbo is probably the most reliable 190mph supercar you can buy, as well as one of the cheapest at around £40k, but should you take the plunge? Does the £200k homologation-special GT3RS deserve a place in collectors’ garages? And where does the 996 fit into the pantheon of Porsche’s greats?

Rewinding a quarter of a century, this most historied of companies was at a tentative make-or-break stage. Its defining 911, 33 years old in 1997, deeply anachronistic and threatened by rivals as diverse as Ferrari, TVR and Honda, could not survive another dubious facelift or mechanical overhaul. Its air-cooled engine was about to fail a new set of emissions and noise legislations. The slow-selling 928 had been pensioned off, as had the 968, the last and least profitable evolution of the 23-year-old 924/944, Porsche’s only real Eighties money-maker.

Porsche’s hopes were pinned a controversial switch to watercooled engines. It also embarked on a new strategy gifted to it at least in part by the welcomed intervention of the Shingijutsu Group. Upon its factory visits in the early Nineties, this team of ex-Toyota engineering consultants found an atelier more reminiscent of Aston Martin than the slick, high-tech image Porsche trades on. The Japanese visitors praised the meticulous skill of the engineers building 911s by hand in the workshop surrounded by shelves stuffed with parts, but as soon as the boardroom doors were closed, their tone changed to apoplexy.

Lean production methods, just-in-time delivery, constant improvement suggestions taken from the shop floor, and shared components – the ‘Toyota Way’ – had to be embraced if Porsche was to survive. In 1996 a new, affordable two-seater roadster, the Boxster, was pitched against BMW Z3s and Lotus Elises.

But waiting in the wings was the 996, an all-new replacement for the old 911. It still packed a rear-mounted flat-six driving the rear wheels of a 2+2 coupé, convertible and Targa range, but it was now water-cooled – much to the disbelief of marque enthusiasts. It also shared whole chunks of its being – including most of the body panels forward of the windscreen – with its cheaper roadster stablemate. Could it possibly meet the lofty standards its predecessor spent more than 30 years setting?

996 Carrera 2

The first impressions of the 996 Carrera 2 nowadays are of both striking purity and perfect ergonomics. Perhaps bashfully, Porsche opted not to badge it a 911 upon launch, opting simply for Carrera, maybe conscious of wanting to move forward and also avoid comparisons with the old 993-generation 911, last of the air-cooled cars, its basic body architecture first seen in 1964.

The Carrera was criticised when new as looking too amorphous, with the headlights coming in for particular scorn for supposedly resembling fried eggs. But in a car-design landscape that’s suffered from some hideous over-detailing of late, there’s a striking purity to an early, basic 996. Neither Harm Lagaay nor Pinky Lai, the 996’s co-stylists, are German, and there’s an internationalism to the way the 996 looks. The severely-angled 911 rump, low tail, flattened nose and froglike eyes of old, rooted in Thirties Autobahn streamliner thinking, are banished by the kind of biodynamism pioneered by Luigi Colani. There’s barely a straight line on it, and in shiny hues the car looks like a flowing collection of oil paint globules artfully squeezed onto an artist’s palette, untouched by the brush. The full-width grille opening up front for the watercooled radiators give it a sly grin that the 911 never had before.

Get up close to the 996 and it feels like a very different car from the old 911. Its bigger for a start – 185mm longer with a 78mm longer wheelbase than the outgoing 993-generation car. The shoulder-line is straighter too, bringing the big old 928 to mind as I slide into its leather driver’s seat. The sense of organic flow seeps into the cockpit, with doorhandles designed Pininfarina-like around finger shapes, and gauges that bubble off from each other in the floating instrument binnacle.

Clutch and brake pedals are mercifully top-hinged, rather than the old 911’s ankle-straining floor-hinged items, and the rake of the windscreen places the car firmly in the Nineties rather than the Sixties. The rear seats are 928-sized too, the higher rear roofline yielding more headroom than old 911s. This overt usability resulted in some rather unexpected comparison tests when the 996 was new – it found itself pitched not only against Ferraris and Lotuses, but also Jaguar XK8s and Aston Martin DB7s. To much domestic consternation, the 996 often beat the Brits in both GT and sports car roles.

It’s time to find out why. There’s a wonderful snort from the water-cooled 3.4-litre flat-six upon the turn of the key, but as it settles to an idle it’s surprisingly quiet, isolated from the cockpit, and near-silent if you stand in front of the car.

The gearshift engages with a snickety, short-travel precision a world away from the Beetley clonk of a pre-1987 911. The original owner of this Carrera selected the factory short-shift option, improving its wrist-flick slickness yet further. My first forays onto the bounding country lanes north of Goodwood reveal an immediate link to 911s past via the beautifully ergonomic steering wheel. Yes, it’s power-assisted, but there’s a sense of unencumbered feel through the leather rim that simply isn’t present in any rack that has to deal with the weight of an engine on top of it as well. Unlike older 911s though, it’s nicely damped, so there’s no threat of a series of bumps, ruts and potholes overwhelming your senses with the feedback. Instead of the nervous fear that old 911s used to generate when pressing on, there’s a newfound sense of confidence in the 996.

But is it still there when it’s driven hard? I happen upon a Morris Minor Traveller of all things, four-up complete with dog, pottering down the A286.

I pull wide, floor the accelerator in third, then maintain speed past the Minor as the road ahead starts to corkscrew. Past 4000rpm the VarioCam system is activated, the actuated tensioners tweaking the timing chains, accessing thrust that leaves hot hatches standing. We’re in head-reeling supercar territory now. This, the most basic of 996s, yours for as little as £10k if you’re feeling brave, offers 0-60mph in 5.2 seconds and a top speed of 174mph. That’s Countach and Testarossa territory. It’s faster than Porsche’s own Eighties wall-poster car, the 930 Turbo. I once did something similar on a country lane in a 930 and soon wished I hadn’t. Having dispatched a hatchback, braking from high speed caused the Porsche to squirm alarmingly, the steering writhing as the rear end threatened to overtake the front. In the 996, there’s reassuring, confidence-inspiring grip from both ends. But it’s not necessarily thanks to stickier tyres – the footprint of the 205/50 ZR17s up front and 255/40 ZR17s at the rear is no larger than an old Turbo’s.

What’s changed is the rear suspension. The wayward trailing arms had already given way to multilink location by the 993, and the 996 uses an evolution of that, five links per side locating its rear wheels with what Porsche called elasto-kinematic toe correction, giving a mild passive rear-steering effect not unlike the 928’s Weissach Axle. It tightens its line even when braking downhill into an S-bend. And yet unlike a 928, the steering never stops talking. This isn’t the 911 declawed, just much more accessible. And that sense of accessibility extends to affordability too. Right now, this is the cheapest way into a Porsche 911 of any kind. As I said, you can find them down at £10k, and they’re better-built than their predecessors too, unlikely to rust unless they’ve been crashed and poorly repaired.

However, buying one has been seen as a gamble thanks to the then-new water-cooled flat-six’s apparently fatal weakness, its intermediate crankshaft bearing and rear main crankshaft seal. Engine designer Rainer Wüst addressed criticism of his unusual design upon the car’s release after eagle-eyed, technically-minded journalists spotted it – camshaft drive for the left cylinder bank was taken from the back of the intermediate shaft, and the right from the front. It was championed by Wüst as a space- and weight-saving measure, but it turned out to place too much pressure on the insufficiently strong roller bearing.

Problem is, a ten-grand car no longer looks like a bargain when its engine can let go without warning to the tune of £7.5k. However, upgraded bearings can be fitted for £800 – a big bill on its own, but a worthwhile precaution that doesn’t add hugely to the initial outlay. You can also be philosophical about it – IMS bearing failure actually only seems to affect about ten percent of 996s and manifests itself long before they clock up 90,000 miles. A well-maintained high-miler that’s had regular oil changes will probably be fine. Probably.

996 Turbo

No mention was made of a turbocharged version of the 996 upon the Carrera’s 1997 launch. It wasn’t the first time Porsche had done this – when the 964 succeeded the K-series (sometimes generalised as part of the so-called impact-bumper G-series) 911 in 1989, it claimed that the VarioCam-boosted performance of the normally-aspirated Carrera 2 and the sheer all-weather point-to-point ability of its four-wheel-drive Carrera 4 sibling rendered the old 930 Turbo pointless.

But with the Ferrari 348tb and Lotus Esprit Turbo breathing down Porsche’s neck, it made sense to keep up appearances, and a new 911 Turbo duly appeared in 1991. The old 993-generation Turbo still hung around on Porsche price lists well into 1998, and was a very different animal, far removed from the old 930. Based on the Carrera 4, it was twin-turbocharged and four-wheel drive like a 959. Crucially, the old car was 10mph faster and a whole second quicker to 60mph than the new 996 Carrera 2. Porschephiles were concerned, especially because they had to wait until the 1999 Frankfurt Auto Show for a 996 Turbo concept to appear, then another two years before they could get their hands on one.

Looking at this 2004 example today, there’s no getting away from its styled-by-engineers ugliness. It looks best in black, simply because the dark paintwork lessens the impact of its huge grimacing grilles, sulky-toddler’s-bottom-lip front bumper and messy two-part rear spoiler that barges clumsily into the rear light clusters. Although the restyled headlights were praised at the time for lessening the fried-egg effect, in retrospect they’re a mess, a chomp taken out of their organic lines leaving an awkward mixture of ovoid flow and jagged edges. The slatted vents aft of the rear wheels nod to the 959, but I really wish Porsche’s engineers had studied that car’s cohesively swooping form more closely when devising the 996’s brutal sibling.

Thankfully, you don’t have to look at it when you’re behind the wheel. The driving environment is identical to the Carrera 2’s, but it only takes a few bends, even at low speeds, to reveal the impression of a heavier car – and it is, by a whopping 240kg, adding the weight of the average motorbike to the mix – with dulled, more distant-feeling reactions from all of the control surfaces. Compared to the Carrera 2, the steering has lost its tactility, the effects of a combination of wide 225/40 ZR18 tyres and a pair of driveshafts up front. There’s also some throttle lag as the turbochargers spool up.

But that’s not to say the Turbo handles badly, especially given the performance. Its sheer velocity creeps up on you unawares while you’re enjoying yourself, making three-figure speeds shockingly easy to attain without really trying. Those driven front wheels bite into bends with hot-hatch incisiveness, gripping hard, never threatening understeer. This encourages me to try and carry that speed through bends, cornering harder as the tarmac loops get tighter towards East Dean, until the tail finally kicks wide. But then, a combination of wide-tyred 295/30 ZR18 rear grip, and the pull of the front driven wheels yanks it back into line. Am I to assume that this what driving a 959 is like?

I must confess at this point that I’ve never actually driven a 959. However, oddly enough the 996 Turbo reminds of another German Group B rallying icon, the Audi Quattro, albeit in reverse. In that car, the engine overhangs the front axle, the car understeers, but the powered rear wheels nudge it back into line. The 996 Turbo’s four-wheel-drive system similarly deals with an apparently imbalanced chassis, but one with the weight at the opposite end, provoking oversteer and tidying the line from the front. It’s effective in its own way, but I prefer the straightforward adjustability of the two-wheel-drive chassis. There’s also a sense with the Turbo that it’s the one doing the driving, you’re just pointing it where you want it to go.

However, this kind of assistance makes it very easy to drive extremely fast indeed. Accelerate hard, and rather than a sudden punch, there’s an extra glissando of turbo-torque that surges in just over 2000rpm and pulls with violent urgency through to 4600rpm. Peak power – all 420bhp of it – is generated at 6000rpm, but this car’s performance is all about surfing that torque wave all the way to 190mph.

And this makes the Turbo, even at twice the price of an equivalent-condition Carrera 2, another bargain right now. Because those are 959 performance figures. But a 959 will set you back £850k and you’ll end up with a car you may well find yourself too apprehensive to use properly, given its rarity and price. The 996 Turbo may not be pretty, but it shares so much with the 959, including four-wheel drive, twin turbochargers and, funnily enough, water cooling (although on the 959 this only extended to the cylinder heads).

But one thing the Turbo has managed to retain intact from the Carrera 2 recipe is that sense of confidence. Yes, it’ll get you into trouble far more readily, but it’ll also bail you out. The grip and ease of high performance is immense – it’s far easier to pilot quickly on public roads than a Ferrari 288GTO boasting identical performance. And the brakes are far better than the Carrera 2’s too. In the normally-aspirated car, while powerful, they feel a bit uncommunicative, lacking in feedback. In the Turbo the braking power is still there, but yet again they imbue the driver with more confidence to use them hard, because the ABS chatters away beneath your right sole.

Another thing you can do with great confidence with a 996 Turbo is buy it. And in no small part that’s because it shared its engine designer, Hans Mezger, with the 996. The late Mezger was responsible for some of Porsche’s greatest – and strongest – racing engines, including those in the 917 and 956. The 996 Turbo’s 3596cc engine is not an evolution of the Carrera 2’s 3.4, but rather a roadgoing version of the mighty GT1 racer’s. It doesn’t suffer the Wüst engine’s intermediate shaft bearing issues, and if properly maintained appears to be virtually unkillable by all accounts. Combined with the rust-resisting, reliable strengths of the underlying 996, the result is a machine that rarely generates scary bills outside of routine servicing, which is a known quantity. It’s unlikely you’ll lose anything of the £35k-£40k you’ll spend on a good one. Although you may need to act soon because that figure is rising.

GT3 RS

The new 996 faced its toughest test of all on track. It was all very well making the road car a semi-successor to the 928, supremely usable and great to drive, or building a Turbo to outgun Ferrari in games of Top Trumps. However, in order to achieve the kind of all-round greatness associated with the aircooled 911s, the new 996 would have to prove itself in competition. The 996 emerged into a golden era of GT racing. Since Group C was destroyed by FIA politicking, taking the World Sports Car Championship with it in 1992, Jürgen Barth, Patrick Peter and Stéphane Ratel seized the initiative and created the BPR Global GT series for supercars. Effectively the belated realisation of the proposed Group B racing series of the Eighties, it saw 911s racing the likes of Jaguar XJ220s and Ferrari F40s, handed a new lease of life by its rules.

As 1997 dawned and manufacturers looked to launch official entries, the FIA officially took the series under its wing, making it professional. Budgets soon spiralled as sports-prototype GT1 and special-production GT2 cars took to the track. In response, the FIA introduced the production-based N-GT class, prompting a new wave of roadgoing homologation specials from 2000. The lightened, track-ready 996 GT3 was created in response, complete with a normally-aspirated version of Mezger’s engine. In 2003, as the 996 was about to bow out of production, Porsche took things yet further with this, the stiffened, higher-revving, lightweight-panelled GT3RS, devised in accordance with ACO30 regulations to take on Le Mans.

In retrospect, if the 996 can be seen as resetting the 911 recipe, thus drawing comparisons with the first ‘901’ 911, then the GT3RS lives in the long shadow cast by the ducktail spoiler of its ultimate evolution, the original 911 2.7 Carrera RS Lightweight. As I pace around the GT3RS, I can find many parallels with its 1972-3 predecessor. Both appeared at the end of the production run of their iteration of 911. Both were built in a batch of 200 to satisfy racing homologation requirements. Both are lightened, stiffened, intense driving experiences with a reputation for being unforgiving. And curiously, both were cheaper than you might think when new. At 34,700 Deutschmarks in 1973, the 2.7 RS was nearly 4000 Marks cheaper than the incoming G-series Carrera.

Likewise the GT3RS similarly undercut the range-topping Turbo. And both RSs have rocketed in price since. In more luxurious and numerous Touring guise a 2.7RS might fetch £450k; Lightweights more like £850k. Meanwhile, at £200k for the best – more than double what it cost when it was new – the 996 GT3RS is well on its way to joining it as a collector’s and investor’s favourite. But should it?

It promises racetrack brutality, from its big adjustable rear wing and aggressively cambered and lowered suspension to its roll cage, fixed-back bucket seats and Alcantara in place of leather. Although it wears Turbo-style headlights; the smaller grilles with the trio of 924 Turbo-style cooling slots leave the nose better-proportioned, somehow balancing racing functionality with genuine prettiness. During Athena’s last twitchings in the 2000s, it put Porsches on bedroom walls again.

And it is very much a functioning racing car with numberplates, rather than some stickered-up limited-edition pastiche. That much is evident as I turn the ignition key and hear the engine thunder through the barely-silenced cabin. The drivers’ seat – tellingly equipped with both a conventional three point seatbelt and a five-point racing harness – is actually comfortable and accommodating, but its hard surfaces buzz and throb with the engine idle. Get it into gear via a markedly heavy clutch pedal and hear its transmission squeal and timing chains thresh as the beast starts to move.

Accelerate, and the modified VarioCam system and Turbostyle Bosch Motronic 7.8 fuel injection system make themselves felt past 3500rpm. So does the car’s relative lack of weight. That said, Porsche, with its use of hefty steel monocoques, has often suffered in comparison with rivals’ use of spaceframes, aluminium and glassfibre. Carbonfibre bonnet, plastic rear windows, a lack of rear seats and stickers in place of badges resulted in a car that weighs 180kg less than the porky Turbo, but it’s still heavier than the basic Carrera 2 with its fully-loaded luxury innards. Admittedly, the GT3RS’s deadly rival, the Ferrari 360 Challenge Stradale, was heavier still, but the Porsche was undercut in the N-GT class by flyweights like the Maserati V8 Trofeo and Morgan Aero 8 GTN.

The Porsche possesses a very cammy engine though, less flexible than the Carrera 2’s. It feels no faster than the base car unless you keep it on-cam, north of 3500rpm, and bear in mind that the modified VarioCam system included in its homologation papers results in its 381bhp being delivered at a screaming 7800rpm. There’s no forced-induction involved, but the feeling under my right foot is not dissimilar to turbo-lag.

But the defining characteristic of the GT3RS is its steering. While the Carrera 2 made traditional 911 wheel chatter safer and more friendly and the Turbo dulled it into numbness, the GT3RS is a return to full-strength communication overload. The ride is firm rather than harsh, but it seems that one of the side-effects of shorter-travel damping, stiffer springs and low-profile 235/40 ZR18 tyres with their slim sidewalls is a car that struggles to cope calmly with anything other than the smooth asphalt of a racetrack. On bumpy B-roads just south of Singleton, the front wheels are dragged in the direction of every undulation and pothole, yanking the wheel violently as they go.

But as the road surface smooths out near Goodwood racecourse, the GT3RS’s track pedigree shines through. Blipping the throttle as I downchange to keep that peaky engine on cam, pace through tight bends is astonishing as the stiffening and lightening programme combines with that trick five-link axle to keep its line tight even at speeds that might seem reckless in a less well-composed car. It also has the best brakes of any of these 996s, both communicative and devastatingly powerful. I’d love to explore its abilities on track.

Not least because it lived up to its Seventies namesake there too. The GT3RSs of Yukos Freisinger Motorsport blitzed the N-GT class of the 2004 FIA GT Championship, winning all but two rounds. However, the car’s most astonishing achievement occurred the year before, when Marc Lieb, Stéphane Ortelli and Romain Dumas took the new GT3RS N-GT car to an outright win at the Spa 24 Hours, beating all the GT-class challengers from the category above, including a mighty Ferrari 550GTS, crushed into second place by an incredible eight laps. A sister GT3RS took third spot on the podium too.

While the GT3RS is one of the toughest 996s of all, combining Mezger-engine vicelessness with two-wheel-drive simplicity, one of the biggest issues is fakery. The mechanical similarities with the GT3 on which it’s based, plus the availability of lookalike RS parts from the aftermarket, combined with the significant value of genuine cars, means RSs are lucrative to counterfeit. YouTube is littered with videos from angry punters who realise they’ve been sold a ringer. Make notes of chassis numbers, cross-check original colours with the DVLA’s database – genuine 996 GT3RSs were only ever sold in white – and get Porsche Club GB’s GT3 Registry involved to authenticate it before you add one to your garage. But in the long term it’ll be worth it – it really is a worthy successor to the 2.7 Carrera RS.

Moment of truth

But is the GT3RS the 996 I’d most like to take home with me? I’d certainly be sorely tempted. There are plenty of cars purporting to be racers for the road, but the GT3RS is the genuine embodiment of this theme. But as a result, it’s totally uncompromising, too intense in its mannerisms for anything other than deeply committed drives, preferably with no-one else on the road.

The Turbo is its opposite. It may also be a 996 but it’s a fundamentally different kind of car, a luxurious, surefooted trans-continental missile, as fast as some V12-powered opposition. It’s extremely effective, but not as fun as other 996s. However, the car that’s surprised me the most today is actually the cheapest. The one with the scary engine issues. The most commonly-found 996. The Carrera 2.

I’ll confess, historically I’ve never been a Porsche 911 fan. I’ve always respected rather than liked them, finding Ferrari’s combination of motor sport heritage, beautiful styling and engaging driving characteristics more intoxicating, and no end of British rivals capable of emulating them on a budget. I love Porsche’s transaxle cars to the point of having owned one, and were someone to have asked me in the early Eighties, as Porsche asked itself, I probably would’ve been in favour of canning the aged air-cooled 911 in favour of a new front-engined range based on the 944 platform. However, having driven the 996 Carrera 2, I will wholeheartedly admit that Porsche was right to keep the 911 concept alive despite its flaws. Because what emerged in 1997 was as flowingly beautiful in its own way as Pininfarina’s finest sculptures, had a chassis that made a rear-engined car finally handle with the confidence of the old transaxle platform, and benefits from genuine, direct motor sport breeding. I’ve already started looking at the classifieds…

‘The car that’s surprised me the most today is actually the cheapest’

Owning a 996 GT3 RS

‘It doesn’t get out much, so thanks for the excuse!’ says Paul Voce of his rare righthand- drive UK-supplied 996 GT3RS. ‘It shares garage space with another white with- red GT3RS, a 997-generation car, which I tend to drive more often. But the 996 is much rarer, with just 200 made and only 25 exported to the UK. And there will be fewer than that in circulation nowadays because some were crashed heavily on track days, turned into racing cars, or exported to collectors in countries which didn’t get them when they were new. By contrast, Porsche made far more 997 GT3RSs [1168, in fact], but they’re less hardcore, and less sought-after. Still great to drive though.

‘They’re very reliable cars – I’ve never had any issues with mine at all, even though it gets laid up and kept on a trickle-charger a lot of the time. However, genuine GT3RS carbonfibre bodywork parts are impossible to come by second-hand if you crunch one — you have to get new door mirror housings made — and there are fakes out there, so the club is your best port of call if you want to buy one.’

TECHNICAL DATA 2004 Porsche 911 GT3 RS 996.2

- As Carrera 2 except: Engine 3596cc horizontally-opposed six-cylinder, dohc per bank, Bosch Motronic M7.8 electronic fuel injection

- Max Power 381bhp @ 7400rpm

- Max Torque 284lb ft @ 5000rpm

- Weight 1360kg

- Performance 0-60mph: 4.4sec.

- Top speed: 190mph

- Cost new £84,670

- Classic Cars Price Guide £160,000-£200,000

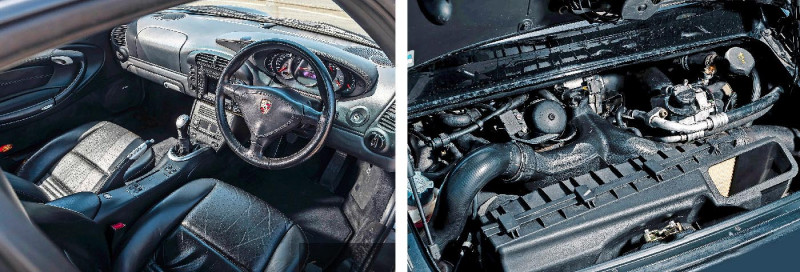

Cockpit comfortable, but race-ready with roll cage and harness. GT3RS engine is normally-aspirated Mezger-designed unit. GT3RS was a 200-off homologation-special roadgoing GT racer.

Best of the Rest

Outwardly distinguished by just a badge on the rear, the Carrera 4 was a four-wheel-drive version of the Carrera 2, following it into production after a year.

Although racing efforts were focused on the normally-aspirated GT3 and its RS evolution, in 2001 Porsche topped the 996 range with the turbocharged GT2. Essentially a return to 930 Turbo-style simplicity alongside the 959-alike 2000-model Turbo, it combined even more power and torque – 462bhp and 475lb ft – with rear-wheel-drive in a two-seater package weighing 100kg less than the Turbo. And on top of that, it was available as a track-ready Clubsport complete with roll cage.

At the end of 2001, Porsche introduced the Carrera 4S. In the spirit of the widebody 911s of the Eighties, this combined Carrera 4 running gear with the beefier bodywork and more powerful brakes of the Turbo. At the very end of the 996’s production run, Porsche finally caved to public pressure and introduced a Turbo Cabriolet, at a €10,000 premium over the coupé. There were also 20 roadgoing examples made of the 1997 GT1 Evo sports-racing prototype, and a single road car version of its successor, the 1998 GT1-98, in keeping with the FIA’s short-lived GT1 rules. However, these were bespoke racers with nothing in common with the 911s they vaguely resembled, although the Turbo and GT3 engines are based on their 3.2-litre powerplants.

Right: GT2 crowned the 996 range, although it did forego the rivet arches of its 993 predecessor.

Left: Cabriolet variant arrived a year after the coupé’s debut, but it wasn’t until the final year of production that Porsche yielded to fan requests for a drop-top Turbo, below. The Evo’s 996-esque front end improved the GT1’s aerodynamics.

‘Its VarioCam system results in its 381bhp being delivered at a screaming 7800rpm.

‘Mezger was responsible for some of Porsche’s greatest – and strongest – engines’

Owning a 996.2 Turbo

‘This car’s suspension has been upgraded slightly – standard Turbo suspension is a bit too soft given the power of the car,’ says Porsche specialist Philip Raby, owner of this Turbo. ‘Saggy suspension is the first sign of wear, especially at the rear near the exhaust where it gets hot. Whenever we get a 996 of any type in nowadays, we typically spend £1200 on the suspension, getting it to drive as it should with new dampers and bushes. When you test drive one for sale, always listen out for clonks.

‘You’re best off spending closer to £40k for a good Turbo that doesn’t need anything doing, but never forget that this is a supercar. The biggest expense they can generate is a failed turbocharger, but it’s rare unless the car has led a hard life, so get a cherished example with a good history. ‘Obviously the Mezger engine in the Turbo doesn’t suffer the IMS bearing failure issue of the Carrera. However, this is also rare. That engine is also used in the Boxster, Cayman and 997 and I have never, ever seen one go. That’s the problem with the internet – everyone’s an expert!’

TECHNICAL DATA 2004 Porsche 911 Turbo 996.2

- As Carrera 2 except: Engine 3596cc horizontally-opposed six-cylinder, dohc per bank, two KKK K16 turbochargers, Bosch Motronic M7.8 electronic fuel injection

- Max Power 420bhp @ 6000rpm

- Max Torque 413lb ft @ 4600rpm

- Transmission Six-speed manual, four-wheel drive

- Weight 1540kg

- Performance 0-60mph: 4.2sec.

- Top speed: 190mph

- Cost new £86,000

- Classic Cars Price Guide £27,500-£44,000

No change here, but Turbo is more GT than raw sports car. Mezger-designed engine is much tougher than 3.4. Bodywork extensions keep Turbo planted on the road to 190mph.

Making them better

‘The basic 996 Carrera 2’s engine doesn’t respond well to tuning,’ says Phil Hindley, founder of championship-winning race team Tech 9 Motorsport, and head of the Liverpool-based UK wing of German Porsche tuning firm TechArt. ‘It isn’t an inherently bad engine, but the scope for improvement is limited. By the time it came to us, Porsche had effectively left it in a very high state of tune already. As a result, all we could do to the engine was limited to sports exhausts, TechArt’s extractor manifolds, and an ECU upgrade chip, all aimed at improving breathing.

‘Although most people probably bought our body conversions for personalisation reasons, they were all tested in TechArt’s wind tunnel before being brought to market to ensure they didn’t hinder performance. We built five 996 Widebodies, with radical extended arches and deep-dish alloys, aimed at road rather than track use, designed mainly to improve roadholding and balance. ‘The Turbo’s Mezger engine was much more conducive to modification though. Our GT Street programme for 996s continues to this day, focusing modifications on three key areas: bodywork, suspension and power, resulting in cars that look like Darth Vader’s helmet! It’s not a case of addressing weaknesses with the underlying car, but its handling is merely adequate when taking into account the power that can be unleashed with a combination of ECU remaps, and TechArt’s bespoke turbochargers, created in conjunction with KKK, plus exhausts and boost control. You need stickier tyres to cope, which in turn need more resilient suspension and bigger, more powerful brakes. ‘We also modified GT3s, drawing on our experience in the British GT Championship, where we were class winners for a number of years. Through this, we developed our own camshaft, exhausts and pistons, and in the early 2000s did quite a few road-car conversions for track-day customers, also recommending our own spring and damper settings for the original suspension to cope.’

TechArt’s ultimate 996 was never used for the purpose it was intended though. ‘Although we raced in the GT3 classes, we fancied contesting the higher echelons of GT racing, and built a 996 with a twin-turbo 962 Group C engine,’ says Hindley. ‘It needed radical modifications to the bodywork to generate enough downforce. However, we couldn’t raise the funds to race it, so a very lucky customer used it as a track-day car.’

Above: TechArt’s racing experience informed bespoke GT3 parts catalogue Left: one of five wind-tunnel-tested widebody TechArt 996s, offering greater stability ‘Darth Vader’- TechArt GT Street Turbos pushed power beyond 500bhp, although a 962-engined evolution never saw the track.

‘It’s faster than Porsche’s own Eighties wall-poster, the 930 Turbo’

Owning a 996 Carrera 2

‘This is something new for me,’ says Jonathan Hampton of his newly-acquired Porsche 996 Carrera 2. ‘Historically I’ve owned Ferraris, including a 456, but I fancied something different this time, and was intrigued by the 996’s combination of genuine high performance – and it is just as fast as my Ferraris – and usability. It promises to be as reliable as a Volkswagen, the rear seats are actually useful, and the fuel economy compared to the kind of supercars it rivals is excellent.

‘People worry about the intermediate shaft bearing failure issue, but in truth most cars don’t suffer from it. The best thing to do to avoid it is to buy a car that’s been used and cared for, with a full service history including scheduled oil changes, and a decent, warranted mileage. If they are going to go, they will have gone by now, making the rarely-used low-milers more of a gamble.’

TECHNICAL DATA 2000 Porsche 911 Carrera 2 996.1

- Engine 3387cc horizontally-opposed six-cylinder, dohc per bank, Bosch Motronic M5.2 electronic fuel injection

- Max Power 300bhp @ 6800rpm

- Max Torque 258lb ft @ 4600rpm

- Transmission Six-speed manual, RWD

- Steering Rack-and-pinion, PAS

- Suspension Front: independent, MacPherson struts, coil springs, telescopic dampers, anti-roll bar. Rear: independent, three lateral & two trailing links, coil springs, telescopic dampers, anti-roll bar

- Brakes Servo discs all round

- Weight 1320kg

- Performance 0-60mph: 5.2sec.

- Top speed: 174mph

- Cost new £64,825

- CC Price Guide £11k-£23k

Spacious, ergonomic interior reminiscent of 928 rather than 911. Base-model 3.4 still packs enough punch to take on Testarossas.996 holds the road with a newfound confidence for a 911.

‘First impressions of the 996 Carrera are of striking purity and perfect ergonomics’

996s on screen

As the 996-generation 911 cemented its position as a profitable, bestselling all-rounder, it cropped up as a guest star in no end of film and TV productions as a quick byword for wealth and dynamism. But there are four famous 996s that stand apart from all the others.

Green-and-white liveried Autobahnpolizei 996s make regular appearances in the long-running cult German police-action TV series Alarm Für Cobra 11. This gritty-yet-daft drama – think Line Of Duty meets Miami Vice on the unrestricted autobahns of Cologne – often saw cops chasing down drug dealers, murderers and thieves with their 996s, light bars flashing and sirens wailing. The series was often criticised for being unrealistic, an accusation which extends to the fleet of Porsches. While 356s and 911s were used to patrol the autobahn in the early Sixties, German police 911s since have largely been used as promotional and educational tools in the fight against dangerous driving, rather than as active service vehicles.

After the 996 debuted in the USA, it received two memorable appearances on the big screen in the summer of 2000. Firstly, a blue Carrera 2 cabriolet starred as Ethan Hunt’s car in Mission: Impossible II, Tom Cruise driving it in a dramatic chase scene as he reels in Thandie Newton’s equally new Audi TT Roadster, ultimately stopping her in her tracks by ramming the Audi off an Andalusian clifftop road. Although set in Spain, the chase scene was filmed in California, with a Renault, Volvo, Saab and Range Rover placed on the road to make it look more European.

Less than a month later, a 996 was the first car to be stolen in Jerry Bruckheimer’s superior remake of HB Halicki’s Gone In 60 Seconds. An early silver Carrera 2 coupé is glimpsed on a podium at a Long Beach Porsche dealership before Giovanni Ribisi’s character Kip Raines steals it, smashing it through a plate-glass wall before tearing off into the night, thus setting up the film’s storyline. If you’re quick with the pause button, you can spot the valuable new car turning into a repainted 1978 911SC for the window-breaking stunt shot.

But surprisingly, the most enduring role for the 996 involved the car as a character itself. In Cars, Disney’s 2006 paean to automotive culture set in a world inhabited by sentient, talking vehicles rather than people, Bonnie Hunt voices a 996 Carrera 4S called Sally Carrera. The character is a former Los Angeles attorney who moves to the small town of Radiator Springs in search of a quieter life. Director John Lasseter based her on Dawn Welch, owner of the Rock Café on Route 66 in Stroud, Oklahoma.

The generational effect on which cars we perceive as classic compared to those merely secondhand is something I’ve talked about before. Probably more than once in over two decades on Classic Cars, so forgive me if I appear to be repeating myself, but celebrating the 996 generation of Porsche 911 as it reaches a quarter of a century makes me feel classic myself. I remember testing a 996 Carrera 4S when it was new, and joining the long queue of journalists to simultaneously praise its huge ability while bemoaning the passage of the air-cooled flat-six engine, compact dimensions and other 911-defining characteristics. As we saw them. Would the new water-cooled wonder ever be revered by enthusiasts not just when new, but at every step of its journey through secondhand status to bargain performer and eventually classic old age?

Well here we are, regarding the 996 in much the same way as we did the SC and Carrera 3.2 of the Seventies/Eighties back then – an affordable entry point to the 911 experience, but not looking or feeling quite dated enough for universal classic acceptance. Well we know what happened to those cars, as buyers too young to be inspired by Sixties chrome started chasing dream machines of their formative years. And now the 996 has set off on the same path, enthusiasts not just settling for them as the only affordable 911 option, but increasingly targeting them out of pure desire.

Certainly the entry-level Carrera 2 still represents the most affordable entry ticket to the 911 cult, but as Sam Dawson concludes, that doesn’t damn it with faint praise. After a day exploring the joys and limitations of the intense and collectable GT3RS, the crushingly quick but greatvalue Turbo and a simpler Carrera 2, you might be surprised by the car he could most see himself owning.

And our special celebration offers even more to complete the 996 picture, including an interview with successful GT racer Jörg Bergmeister, plus sections on its role in film, tuning and more. Enjoy the article.

GT3RS, 911 Carrera 2 and Turbo makes the case for 996

Porsche 996 frailties

You didn’t mention the Porsche 996 cylinder bore scoring (Porsche 996 at 25 years), another known issue for the 996 and first generation 997. It’s serious, costly and painful. Early 996s (3.4s) had gearbox issues and 996s tend to eat radiators too.

I own a 993 C2 manual coupé and so I was surprised that Sam Dawson quotes the 996 as ‘better built than their predecessors’. I think he’s seeing that from only one perspective, the body perhaps? Granted that key areas of an Eighties 911 — kidney bowls, sills, B-pillars – would rust from the inside out but I reckon the aircooled engines were more robust.

If I were looking at the Porsche 996 era, it would be a 986 Boxster because it’s lighter and more fun to drive in the 3.2 form, though they do suffer the same type of issues as the 996.